Nonprofit leaders often create their boards purely because they have to or because it was foisted upon them. They don’t see their boards as crucial to their organizations’ success. In this two-part series, you’ll learn how to better conceptualize nonprofit boards and find the right tools to organize them into successful contributors. The first part identifies who should be on the board, while the second part explains how to organize the board to improve efficiency.

Table of Contents

Overview

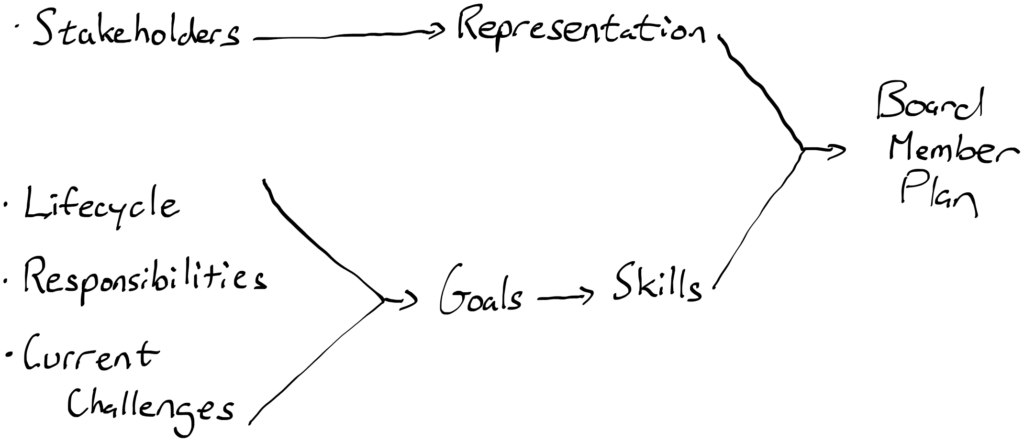

The approach entails creating a plan regarding the types of board members that require recruiting. The first step is to identify the stakeholders of the organization and plan how they are represented on the board. Second, you should consider where the organization is in its lifecycle, what challenges it is experiencing, and what responsibilities a board has. Those items feed into the goals of the organization which informs the skills needed. The representation, skills, and goals then give rise to the board member plan.

Stakeholder Representation on a Nonprofit Board

The first step in building a better board is understanding nonprofit stakeholders. A board needs representation from all of its stakeholders, and those stakeholders should all have a voice on their board and thus be represented. Specifically, five common stakeholders should be represented on a nonprofit board, namely:

- Community members: boards should ensure the communities they serve are represented. Community members provide valuable input on their specific needs, how the organization’s mission can be achieved better, and how to ensure their lived experiences are accounted for in service delivery. A core challenge is that community members may not have the time, energy, or financial wherewithal to participate in a traditional board structure. Nonprofits should therefore be creative in how they enable members to join and participate on boards. That might entail paying for lost wages, providing childcare, or finding alternative forums and systems for members to voice their concerns.

- Executive director and staff: nonprofit boards should include staff and management, since they operate the organization. They are the on-the-ground experts regarding the daily operations of the organization. Smaller organizations will usually require that all staff members attend board meetings, while larger organizations will often only have department heads, or specialists whose expertise are required, attend. Staff members have an important voice and can be radically affected by the board and its decisions. It’s therefore crucial for them to be connected to the board and be heard.

- Funding bodies: it’s crucial for boards to include funders since these organizations, grantors, or individuals usually contribute significant amounts of money to a nonprofit. However, this group is a tricky one for a board. Funders often want to stay informed, but don’t necessarily want to participate directly in organizational activities. I would not include such funders on a board. On the other hand, funders who are interested in networking with other funders, or have beneficial expertise or insights, can be a huge boon to an organization.

- Volunteers and experts: nonprofit boards should ideally include volunteers and other experts with a long-term commitment to the organization and its ideals. Volunteers are similar to staff in that they often have the best boots-on-the-ground viewpoint of an organization, as well as a broad perspective on how to optimize activities. Additionally, a board may require special expertise—for example, a doctor for a medical support nonprofit, a veterinarian for an animal shelter, or an accountant to manage the finances.

- Partnered organizations: the final stakeholder, partnered organizations, are those who are in strategic alignment with the nonprofit. For example, an organization involved in housing the un-housed may partner closely with a food bank to better coordinate aid and service delivery. By being on each other’s board, they can ensure their operations continue to complement one another.

Once you understand a nonprofit’s stakeholders, you can start mapping out how each stakeholder is represented on the nonprofit board. This representation might require different structures, cadences, or input into the board. Perhaps some are involved in board committees but not specifically on the board, or perhaps some are key role players and should be on a steering committee.

Lifecycle of Nonprofit Organizations

Nonprofit organizations need different skills, abilities, and personalities based on their type of service, but this also depends on where the organization is in its lifecycle. Nonprofits in the startup stage often need a very dedicated and hardworking board, while a more mature organization often needs an established network, and access to continued and stable funding. When trying to organize and recruit for a nonprofit board, an organizer must consider how the lifecycle influences where the organization lands.

Nonprofits that are just starting out must verify that their concept holds water, bootstrap their operations and services, build networks to raise funding, and find a path to sustainability. This requires a lot of hard work and most startup organization have very limited funding. So, a nonprofit in startup must rely on a cadre of very dedicated volunteers who are committed to seeing the organization succeed. This working board approach isn’t sustainable in the long term—maybe one or two years at best—because working board members will rapidly burn out from volunteering many hours of their precious free time, apart from their own jobs and family obligations.

Nonprofits who are more mature and have reached a degree of stability should have funds to hire staff and outside assistance to perform most of the regular operating tasks. The tradeoff is that the nonprofit requires sustained funding to finance operations. The board shifts from a working board to a sustaining board, and a different skillset becomes more important. Board members’ access to potential funders become more critical, while the time volunteered per board member reduces, and the board becomes an operation.

Nonprofits who are either growing or shrinking might need a hybrid board with a mix of skills. On one hand, the core organization may be stable and have the requirements of a mature nonprofit. On the other, a portion of the organization might be in a growth phase. In that case, a subcommittee or a group on the board may require the skills and commitment of a working board.

So the second step to building a better board is to understand where an nonprofit is in its lifecycle, what the goals are in that lifecycle, and what skills are needed.

Roles and Responsibilities of a Nonprofit Board

Contemplating specific board roles and responsibilities is the next step. This includes legal considerations, such as requirements pertaining to board member actions and liabilities, as well as practical concerns, such as specific activities the nonprofit requires from its board to maximize efficiency.

First, a nonprofit board is almost always responsible for the hiring, firing, and performance evaluation of the executive director. The executive director runs the organization on a daily basis, builds and executes strategy in conjunction with the board, ensures service delivery, and is almost always heavily involved in fundraising. Most boards also usually participate in advising the executive director, and providing a source of guidance and direction.

Second, a nonprofit board provides the organization’s financial and legal oversight. Board members are the last line of defense on financial and legal matters. Moreover, especially in small organizations, they may be one of the only checks to ensure financial transparency and accountability from the executive director. The board should also ensure that the right people—accountants, lawyers, and the like—are engaged where they’re required.

In the United States, most nonprofits are required to file a yearly tax return—usually form 990. The 990 requires financial statements, lists of major donors and board members, checks to ensure the nonprofit is compliant on items like lobbying, and checks of best practices, including conflict of interest-, whistleblower-, and joint venture policies. States often require additional filings. The 990 and state level filings are some of the most important compliance items. As such, a board must ensure that these documents filed in timely manner.

Finally, most nonprofit boards are usually heavily involved in the organization’s larger strategy. The board is the ideal place to build out and organize yearly and quarterly goals, consider partnerships, and plan new or modifying services, since it represents most of the active stakeholders. The board will often coordinate this effort in conjunction with the executive director and the wider range of stakeholders.

The current challenges faced by the nonprofit

Understanding the nonprofit’s current situation forms last core element.

The nonprofit’s short-term challenges constitute the first item. If the organization is in a cash crunch, then the most important people to onboard are perhaps folks with good connections or fundraising skills. Similarly, if a key staff member with a lot of operational knowledge leaves the organization, then it might make sense to add a long-term volunteer with similar operations knowledge. They may or may not need to be full members of the board. Often, a volunteer might be happy to be on a committee, but not the full board. Or they might be happy to report to the nonprofit board regularly in the short term, but would prefer to only check in once a quarter in better circumstances.

A nonprofit can also face medium to longer term challenges. One example might be a change in legal rules that necessitate changing the operation’s behavior. In that case, it might make sense to add someone with a legal background to help steer the organization through the compliance challenges. These longer-term goals usually require that the board maintains a sustained impact. Thus, it makes more sense to add a board member who can focus on the challenge.

Putting it all together

Now that the representation and skills required have been identified, understanding who should constitute a board becomes clearer. To make it even easier, I’ve put together a board planner here.

The first step is then to either consider the existing boards’ makeup and what gaps are present, or if starting from scratch, what is needed to get the organization moving. Drafting a list of potential members is the next step. Care should be taken that each key stakeholder group is well represented, and ensuring that the right skill sets are onboarded to meet the responsibilities and challenges facing the board and organization. Finally, it’s crucial to ensure that a board gels as a cohesive unit. Any potential board member’s personality should be evaluated on whether they’ll be a good fit in the organization and board.

Check out the next post to find out more on how to organize the board.

Leave a Reply